'Oppenheimer' reignites debunked arguments in support of nuking whole cities

At minimum, Oppenheimer succeeds in starting a conversation, yet ultimately still falls victim to parroting debunked and dangerous narratives

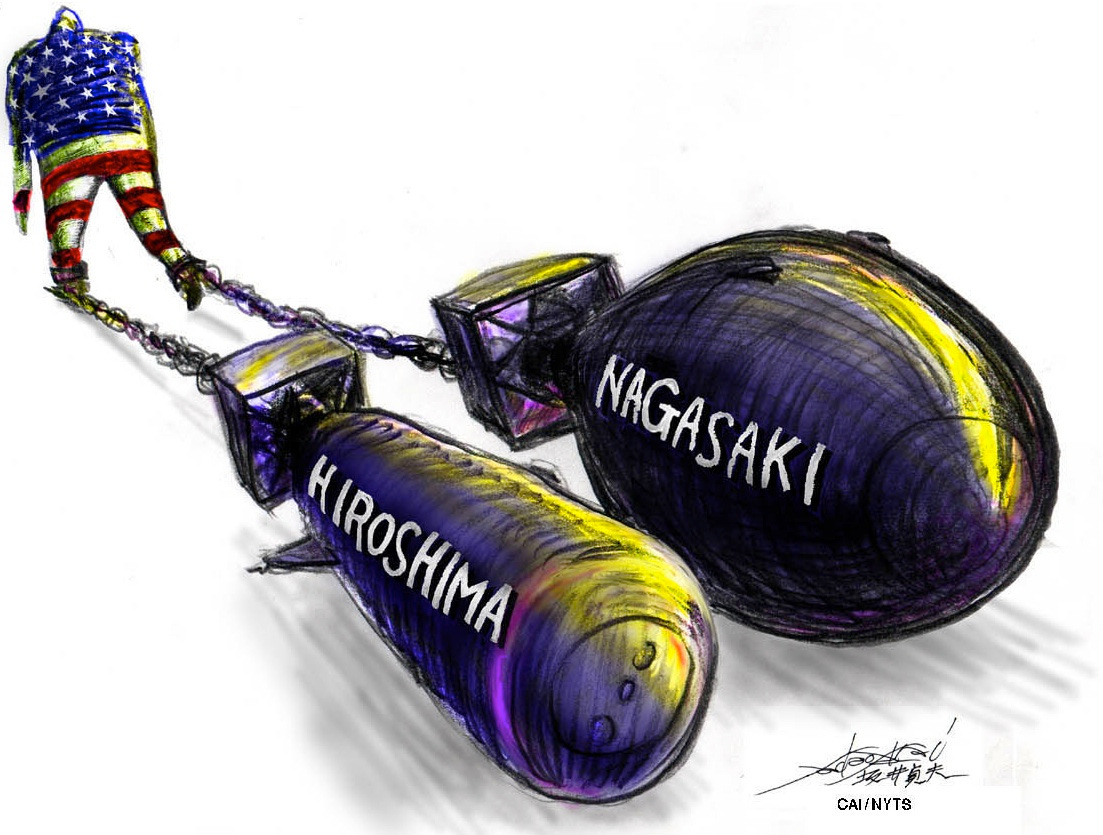

I finally got around to seeing the Oppenheimer biopic this weekend, fully expecting to be met with debunked talking points about how dropping nuclear bombs on Japanese cities was absolutely necessary. In this regard, I was sadly proven correct, and while I was mildly pleased to see a very slight counterbalance depicting atomic horrors, none of these depictions involved images from Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or the unfortunate civilians on the ground.

Perhaps worse, the film’s release has seen the emergence of the kind of crowd eager to defend to the death America’s right to nuke cities without remorse, partly justified by an “all is fair in love and war” mentality and partly justified by exhausted arguments that it was the only other option aside from a ground invasion where millions of young men would be sent to die.

First, even if one believes “all is fair” in war, eventually that war will come to an end, with that war’s winners being the judge as to how the losers handled themselves. Such was the case with Germany’s defeat, where genocidal Nazis found themselves noosed up and swinging by their necks, and such may have also been the case had the US lost the war after instantaneously vaporizing over a hundred thousand Japanese citizens with atomic weapons in the span of roughly 72 hours. Our “debates” around whether the bombs were necessary - let alone a war crime - are a sick privilege only afforded to us because we came out on top, with minimal credit for that victory owed to the use and development of nuclear weapons.

But the more prominent and overwhelming viewpoint expressed in Oppenheimer paints the nukes as a “necessary evil” essential to quickly ending the war, an argument strongly at odds with both historical fact along with some pretty heavy hitters in the World War II scene.

For example, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied commander in Europe during World War II, recalled a meeting with Secretary of War Henry Stimson, where, "I told him I was against it on two counts. First, the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn't necessary to hit them with that awful thing. Second, I hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon."

Eisenhower’s views were given further credit in 1946 when the US Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that, “based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”

Others involved in the war effort expressed similar views. For instance, the personal pilot of General Douglas MacArthur recorded in his diary that MacArthur was "appalled and depressed” by this “Frankenstein” monster. MacArthur believed that Japan would have surrendered as early as May 1945 had the US had not insisted upon unconditional surrender, with his biographer, William Manchester, writing that he knew the Japanese “would never renounce their emperor, and that without him an orderly transition to peace would be impossible anyhow, because his people would never submit to Allied occupation unless he ordered it.” He went on to point out that, ironically, when the surrender did come, “it was conditional, and the condition was a continuation of the imperial reign. Had the General’s advice been followed, the resort to atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been unnecessary.”

Admiral Leahy, Truman’s chief military advisor, wrote in his memoirs: “It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”

Admiral William Halsey, who participated in the US offensive against the Japanese home islands in the final months of the war, publicly stated in 1946 that "the first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment." The Japanese, he noted, had put out a lot of peace feelers through Russia “long before" the bomb was used.

Yet, such peace efforts were ignored, and instead, Japan became a showcase for the United States to demonstrate its new power to the Russians: “If the bomb won the war, then the perception of US military power would be enhanced, US diplomatic influence in Asia and around the world would increase, and US security would be strengthened,” writes Ward Wilson over at Foreign Policy. “The $2 billion spent to build it would not have been wasted. If, on the other hand, the Soviet entry into the war was what caused Japan to surrender, then the Soviets could claim that they were able to do in four days what the United States was unable to do in four years, and the perception of Soviet military power and Soviet diplomatic influence would be enhanced.”

As such, on August 6th, and again on August 9th, the bombs were used against Japanese cities.

“The entire population of Japan is a proper military target,” Colonel Harry F. Cunningham, an intelligence officer in the US Fifth Air Force, said in a July 1945 report. “There are no civilians in Japan.”

Similarly, there were no Japanese civilians featured in Oppenheimer, nor any footage of the bombings. Instead, the film lazily regurgitates the tired narrative that these cities had to be nuked to end the war, with director Christopher Nolan perhaps spending more time focusing on creating a nuclear explosion without CGI than effectively demonstrating why using these weapons was entirely unnecessary.

“We intend to demonstrate [the bomb] in the most unambiguous terms - twice,” says Matt Damon in the film, playing the part of Lieutenant General Leslie Groves. “Once to show the weapon’s power, and the second to show that we can keep doing this until Japan surrenders.” James Remar, playing Secretary of War Henry Stimson, then points out the US has a list of “twelve cities” to choose from. “Sorry, eleven. I’ve taken Kyoto off the list due to its cultural significance to the Japanese people. Also, my wife and I honeymoon there.” That last line may have been added in for comic relief, which it succeeded in evoking from some in the theater during my visit despite feeling wildly inappropriate given the topic at hand.

Remar’s character then adds: “According to my intelligence, which I cannot share with you, the Japanese people will not surrender under any circumstances, short of a successful and total invasion of the home islands. Many lives will be lost, American and Japanese. The use of the atomic bombs on Japanese cities will save lives.”

Ultimately, my issue with the film has less to do with getting history wrong and more to do with making sure it isn’t repeated. In the absence of refusing to wholeheartedly condemn the use of nuclear weapons, we are left with moral ambiguity around their use. Sure, these weapons might be terrible, but maybe, sometimes, it’s okay to use them. And if we can be propagandized into believing that using nuclear weapons against cities is sometimes necessary, the limits are truly endless on what else we can be propagandized into supporting.

If we’re not drawing the line at nukes, we’re definitely not drawing the line at wholescale invasions of countries based on false claims, at waterboarding and other forms of torture, and at drone strikes on weddings and funerals. We’re not drawing that line anywhere meaningful if it doesn’t at least start with a refusal to stand behind nuking whole cities, and in a country with a vast biochemical and nuclear arsenal, with military bases on every corner of the planet, and with a long record of brutal coups and interventions, this is truly asking for the absolute bare minimum.

Oppenheimer succeeds in starting a conversation around this topic, yet still ultimately falls victim to parroting narratives that risk leaving viewers not entirely convinced that these weapons should never have been used, and should never be used again.

Amazingly well written. I found your article from AntiWar, excited to read more of your articles.

In the late 1990s I hosted a 16 year old Japanese exchange student for a year and I took her to see the Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. Much to my surprise, there we saw the Enola Gay airplane. At the end of her visit she presented me with 1,000 cranes on strings which I still have. Looks like the US celebrates the atomic bombing of Japan.